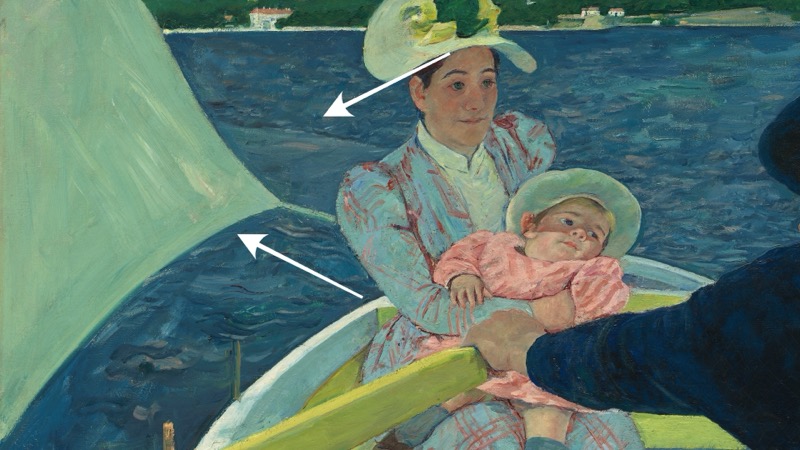

By putting a baby right in the middle of her painting, Mary Cassatt goes against a conventional wisdom which advises us against placing such an important focal point in the center of the image.

This painting, The Boating Party by Mary Cassatt, comes from a time when she was both spending summers on the Mediterranean coast and she was also influenced by Japanese prints. And these two combined may account for some of the strong colors and simplified shapes that we see in the painting. But really these things don’t tell the whole story. There’s so many things that she’s doing. The way that she tips the boat up so we can see into the boat. The way she moves the shoreline back, thus activating the whole space. The way she’s using the sail, the way she’s painting the water. All these different ways of activating space. The way that people are looking towards or away from each other and not quite to each other. It’s a really fascinating painting and we’ll look at all of this in depth in this video.

Cassatt has used a number of techniques to create a wonderful painting. A painting that creates great pictorial space and movement, giving rise to harmony and tension through the use of space and color. We’ll start with the arrangement and treatment of the objects in the painting, before moving on to look at colors in a following post. We’ll start by looking at the relative positions of the figures in the painting. How their interactions and spacing works to create tension in the piece. How elements such as the sail and the oar affect the space.

Here we can see the child sitting right in the center of the canvas. True, it’s a little bit higher vertically than center, but still it’s very centrally located. This is supposed to be about as big of a no-no as there is. We’re always told, do not put the focus in the center of the composition. Nonetheless, the baby is right in the center of the painting. And the woman, whom I presume is the child’s mother, sits just to the side, very close to the center as well. The problem generally associated with putting a point of focus right in the center of the space is that it can cause us to focus only on the center and not move around the space and take in the full work. Of course, there are ways to deal with this.

We often see portraits with a person in the center of the work. Artists such as Rembrandt and da Vinci had ways of dealing with this, mainly through shifting the background space to create movement around the person. We’ll look more closely at them in the future. How does Cassatt create movement in this work, despite having a principal point right in the middle of the composition?

In Henry Rankin Poore’s excellent book, Pictorial Composition and Introduction, he says, “The baby is the focal point or pivot round which the figures and the objects almost visibly revolve. Note how the oar and the man’s arm effectively are carried over, the line of the oar to his hat, the line of the arm through the sail.”

While we can see this movement in the work, it’s as if there’s a big X moving through the piece. It hardly tells the whole story of the painting. There’s a lot more going on in this painting that’s worth looking at.

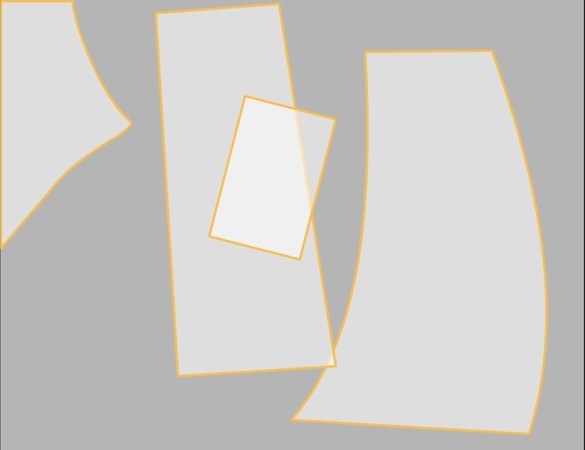

Cassatt creates a very active and dynamic pictorial space through a number of brilliant techniques. This causes the whole painting to come alive and breathe with harmony and tension. If we look again at the painting, the way the mother is sitting and holding the child is a little strange and frankly, it doesn’t seem very comfortable. If I were sitting on a boat holding a baby, I’d probably try to sit in a safer and more comfortable way. Probably securing the baby against my body instead of holding the baby’s head kind of hanging out away from my body. But, artistically speaking, it’s wonderful. Why is that? Let’s turn once again to a simple planal map. I introduced the idea of planal maps in a previous post where we discussed Whistler’s mother.

If we look at this in terms of their planes, we can see that what Cassatt has done is subtle and really quite brilliant. She’s created movement by putting the mother and the baby at angles to each other.

The opposing movement from each of them creates diverging lines of movement in the center of the painting. And so, even without looking at the sail or the oar or any other aspect of the painting, we see that Cassatt is already creating interest and movement.

If she hadn’t, if the baby were sitting comfortably in the mother’s lap, as we’d probably prefer in a boat ride, if they both line up, then suddenly there’s much less movement and the composition is more static.

Even worse, if they were both sitting straight upright, then we’d really have a much more static composition. And this would really cause us problems with them both being centrally located and static in their movement. The painting would become stilted, lose its sense of movement, and become much less dynamic.

We see other artists put important objects in the center of their paintings as well. Here we see Degas puts a large mirror in the center of his work. Just as with Cassatt, Degas had to devise a way to offset the central position of the mirror in order to create movement in the work. In Degas’s case, he was probably not going to set a heavy mirror down on a precarious angle where it might fall, as Cassatt did with the child. So instead, he came to an ingenious solution.

He added an extra dancer into the mirror. While this dancer does not seem to exist anywhere else in the work, she does serve the important service of adding weight and movement to the composition, thus preventing it from becoming static and potentially keeping it stuck in the center, with our attention focused only on the mirror.

In Cassatt’s The Boating Party, another important aspect of the relationship of the figures is their proximity to each other. They are all positioned very close to each other, with only a small amount of space between them. Their proximity and the different ways they are leaning and moving also provides for a dynamic area of negative space between them.

As we can see, not only are the woman and the child at angles, as we just discussed, but Cassatt also painted the boatsman from an unusual point of view. In a painting, we often see figures either straight on, seen from the side in profile, or maybe at a three -quarters angle. In this case, Cassatt has painted the boatsman at a much more extreme angle.

We barely see just a little bit of one eye. She’s manipulated the nose, perhaps a little bit out of perspective maybe, but she manipulated it to make sure that we can read it as a nose. And she’s made sure that his body is angled just enough so that she can put his leg up in a way for us to read it clearly as such. No doubt, this was not easy to paint, and she’s perhaps taken a few artistic liberties with perspective and anatomy. But it was all done in the service of creating an active space in her painting.

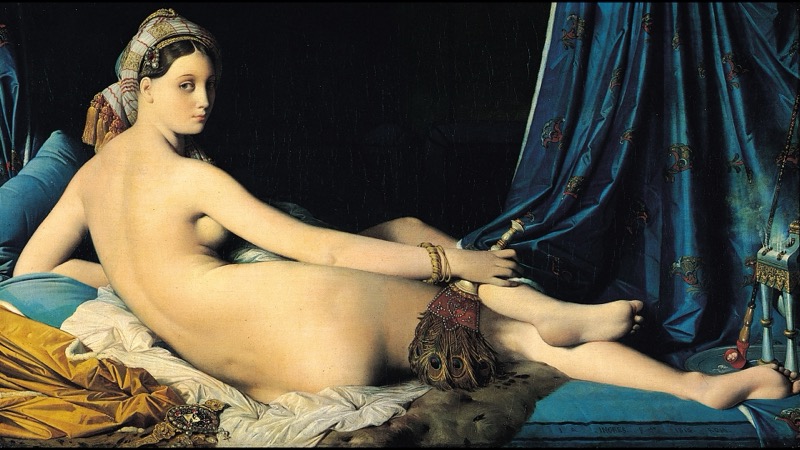

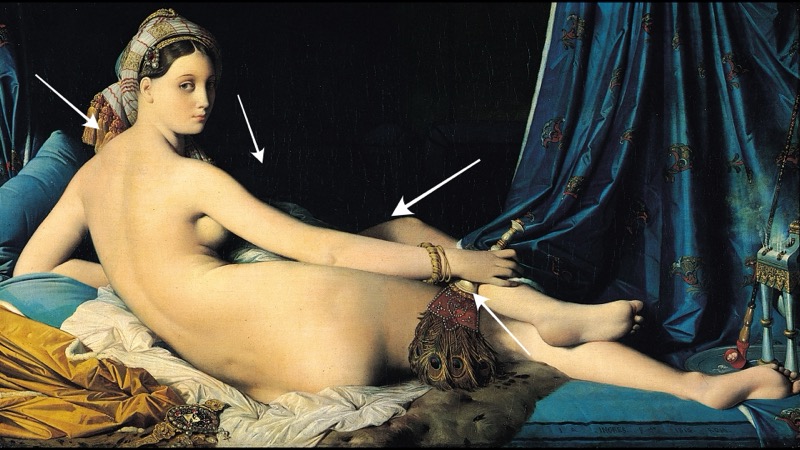

We’ll see that time and again, artists will do this. They’ll sacrifice absolute realistic accuracy in order to create the pictorial space that their work calls for. We can even see that in the painting, the Grande Odalisque by Ingres. This is a very classical -looking painting. And yet, we notice that the woman in the painting is painted in a way that we’d be hard-pressed to say is perfectly anatomically accurate.

The back is far too long, and overall, she seems to be lacking in several bones, making her body unusually elongated and fluid in a number of places. Of course, all of this was done in the service of making a fine composition and a beautiful painting.

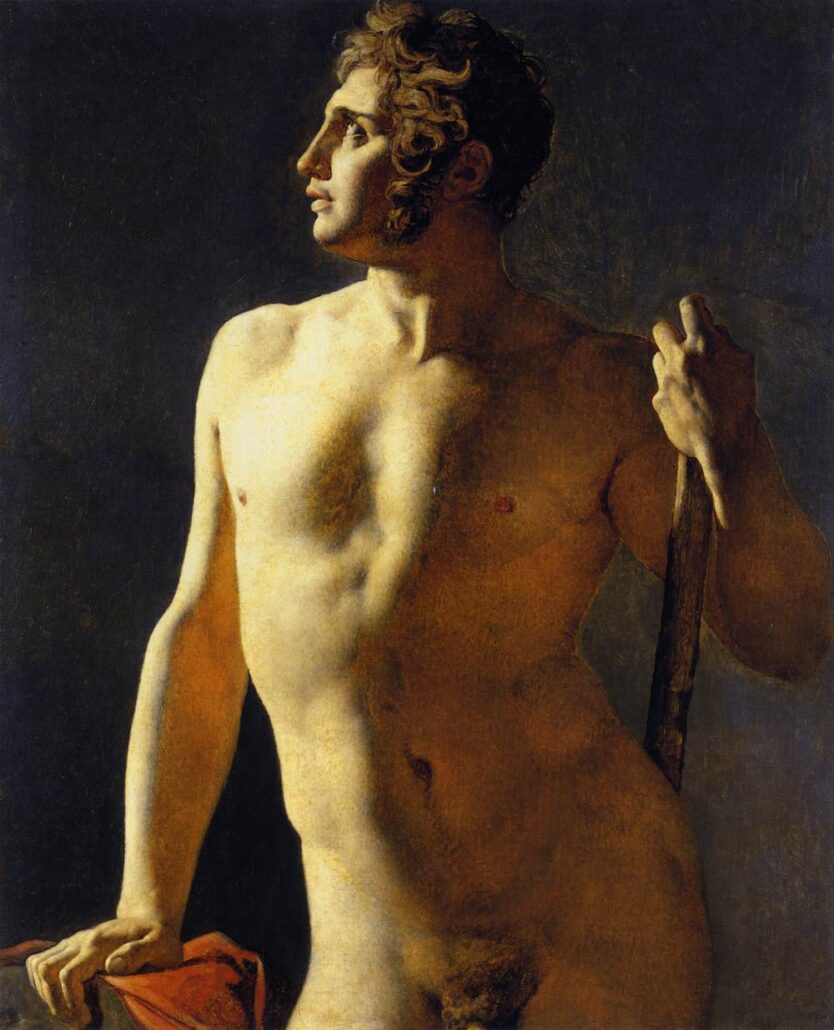

We can see, other work by Ingres showing clarity and accuracy of anatomy. So we can see that he was clearly capable of creating an accurate anatomical painting. But he was also capable of manipulating the figure to create the space in the composition that he wanted. And this is a far greater artistic achievement that requires at its base the ability to paint and draw accurately anatomical figures. But also the ability to modify them, to create the space in the composition that the artist is looking for.

The mother and the child seem to be looking off to the side of the boatsman. While the boatsman may be looking off towards the sail, we see just a bit of his face, just enough of a hint of his eye to get a hint of where he might be looking. And just enough of the right leg, leaning on the bar of the boat, so that his body appears as a curve, rather than a straight line.

If we remove his leg, well, that is to say, if we take his leg out from the painting, he still has his leg. We’re not cutting his leg off. We’re just imagining what it would look like if he had been painted in a way that we don’t see his leg. So, if we remove his leg, he then appears much straighter. So, we can see that the detail of the leg significantly helps in the movement between the figures and the space of the painting as a whole.

This easily overlooked detail of the position of his leg helps to create this curved movement, which works in conjunction with the angled planes of the mother and the child.

These movements, combined with the cross-directionality of their gazes, adds not only to the movement of the piece, but also to the overall tension of the work. From their body positions, to their gazes, and even to the water, this does not feel like an overly tranquil scene. Not outwardly hostile or violent, but under currents of tension and something somewhat uncomfortable. This is in contrast to similar, but more tranquil scenes from artists such as Manet and Caillebotte. After all, these boating scenes, often carrying titles such as the Boating Party, are meant to refer to leisure time activities. So, we’re usually not looking for a lot of tension in these paintings. And the feeling in these works is much different, much more serene, more of a feeling of a relaxed day on the water, befitting the name Boating Party. So, Cassatt’s take on this theme is a little bit different in this way. We’ve been talking about the positions and postures of the people depicted in the painting. But there’s something very important that affects all of this, which is a relative spacing between each of them.

The distance between them is important. After all, we’ve been talking about their body language, their positions, where they’re looking. These small movements and indications, these wouldn’t transmit across long distances. If you and I are sitting together on a bench, and shifting slightly away from each other because of a small tension, this would be quite noticeable. But, if we’re sitting further apart, maybe at different tables at a cafe, it would be very hard to notice, and we probably wouldn’t even pay much attention to it, or really care about it very much at all.

Similarly, the close distance between the figures in Cassatt’s painting plays an essential role. We’ve talked about the way the mother and the child are leaning, and the subtle movements of the boatsmen, as well as the directionality of their gazes. We can see that the figures in Cassatt’s painting retain a very close relationship to each other, creating an interesting and exciting negative space around them. On the other hand, we might also feel that the space in the boat is a little bit crowded.

If we create a simple planal map of the figures in the painting, we can see that they’re quite crowded together, with only a little bit of space between them.

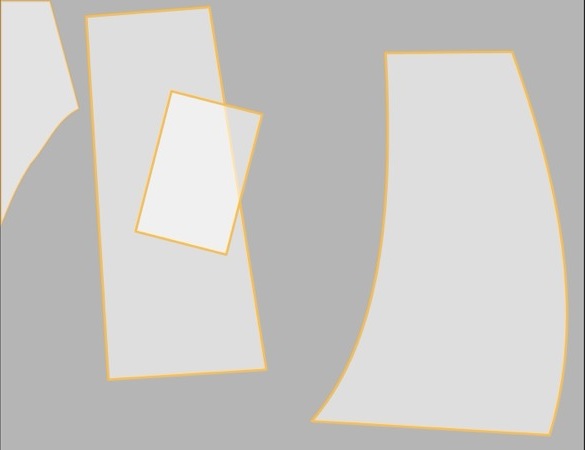

If we move them apart and separated them, all of this would become much less relevant. By separating the figures further apart, the subtle indications of their relationships decreases. It becomes a situation of the mother looking to one side of the scene, and the boatman looking out in the other direction, perhaps at the sail, but not an awkward situation of them looking past each other. It’s interesting to note that the second, more separated version of the planal maps, the version that would be less effective in this painting, that’s the version that actually follows the rule of thirds, while Cassatt’s original painting does not follow the rule of thirds.

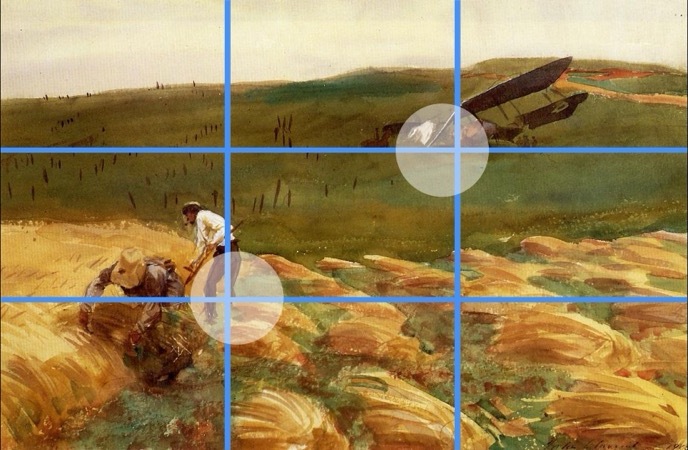

We tend to hear a lot about the rule of thirds, and many people will tell us that we should use it in our compositions. The rule of thirds is a way of positioning the important features of a painting into the cross points of the space, when divided into thirds, such as that delineated by a grid, as seen here in this painting by John Singer Sargent, where the feet of the man working in the field and the part of the airplane both touch the crossing lines, one in the upper right and one in the lower left. The rule of thirds is a common way to organize the elements in the painting, and, while it can be useful, it’s certainly not applicable in all cases.

She’s also tipped up the space in the painting. We feel like we can step into the boat, and it feels as though we’re looking down into the boat. This allows the boat to take up a majority of the space in the painting. We talked about tipping up more in detail in my post on tipping up. Tipping up the boat might seem odd, perhaps an extraneous detail or maybe even some odd detail that I alone would like to point out. However, in this painting, the tipping up of the boat is essential.

If she hadn’t done that, if she’d use a more conventional, linear perspective, a straight-on approach such as this painting by Winslow Homer uses, in that case, we wouldn’t even see into the boat.

Even a slightly raised-up vantage point, as in Manet’s painting, doesn’t put us inside the boat in the same way. And so we wouldn’t feel the interactions of each of the figures in the painting as closely and as directly.

Tipping up the boat in this way puts us near to being inside of it. And so we feel the looks, the shifts, and the leaning of each of the figures that much more intimately.

There are other things that keep the space moving as well. The sail is one of the more interesting and animated characters of this piece. It’s painted at a very dynamic angle. Not only does this angle excite the space, as Rankin Poore alluded to, it leads us to the woman and the child in the boat. This directionality is aided by the oar, which points right to the child and combines with the sail to compress the space and speed up our movement towards the mother and the child.

This speed of movement is also helped by the brushwork and the handling of paint. Although a lot of the water is very rough and has a lot of brushwork in it. In this area, Cassatt has painted a lot of the water in a much smoother way, thus allowing the eye to move quicker over the space with much more directionality, following the shapes she has created in the water. I used to wonder why exactly does this boat need a sail when it’s a rowboat. Researching for this video, I found out that they actually did have rowboats with sails on them at that time, which surprised me a bit. Regardless of that, whether or not the boat needs a sail, the painting sure does. The way this sail functions in the color and the space of the work is vital.

If we remove the sail, we’re now faced with a large empty space which I feel like I could fall into. My attention suddenly moves from the mother and the child to the large expanse of water on the left. So the sail is actually funneling our attention towards the mother and child. This makes me realize that the sail is actually acting as an arrow pointing to the mother and child.

If we leave the sail in but remove the oar, the difference is not as great. There is still a change. We arrive at the mother and child more slowly, but we still get there. Whereas without the sail, well, we’ll certainly still find them. We may end up slipping away. They end up feeling somehow a bit less important and less active.

There’s one more detail that we haven’t talked about yet. One more change to the work, but this time not a change that I’ve made. Since we’re looking at this work online, we need to be attentive to the digital version of the painting that we’re looking at. If we look at the painting on the National Gallery of Art’s website, we can see here on the far side of the boatsman that we can also see the green of the boat. Whereas with the version from the Google Art Project, the painting has been cropped and we don’t see that. I think that having discussed this painting as we have, that you can probably see how this changes the overall sense of movement in the piece, preventing the space from fully circulating around the space of the image. So even though we’re only looking at this digitally, it’s still important to try and get as good of a representation of the work as possible. That’s why I appreciate so much of the work done in getting us good images of artwork. Without them, it would be so much harder to learn from and about all the wonderful artwork that we talk about here.

This painting by Mary Cassatt is really amazing. There’s so many things happening with the shoreline and the tipping up of the boat, the way the sail is handled, the way the water is handled, the way the people are looking. There’s so much going on. And I think that the more that we understand it, the more we can feel. And I think this is really important in that I’m going through these different things that are happening. Maybe I’m explaining it, it seems a little technical. The shoreline, the movement, the tipping up and these things. But the reason that I want us to understand it so clearly is so that we can feel it better. Now, if you’re an artist, as I am, it’s important to understand it so that we can do it in our own work if we want. Whether painting it exactly the same way or something different or what have you, but that we can understand it to implement it. But as an art lover, which as an artist, I think we also are art lovers, we want to feel it. And I think that the better we understand it, the better we’re able to see what’s happening, then we can take that, we can acknowledge it, we can see that’s there. And we can then really feel it even more deeply. We can read it better. We can hear what it’s saying even more fully and more deeply.

Artwork:

Link to Mary Cassatt, The Boating Party at the National Gallery of Art https://www.nga.gov/artworks/46569-boating-party

Edgar Degas, The Dancing Class

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436141

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, La Grande Odalisque

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grande_Odalisque

John Singer Sargent, Crashed Aeroplane

https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/23727

Winslow Homer, Boys in a Dory

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/17053

Edouard Manet, Boating

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436947