Pieter Bruegel’s painting, “The Harvesters,” is really very unique in terms of how it handles space. This painting, The Harvesters, was painted by Peter Bruegel in 1565. Painted on wood, it’s a fairly large painting, almost 47 inches by 64 inches, or 119 by 162 centimeters.

Bruegel was from the Netherlands. The painting was commissioned by a merchant, and perhaps owing at least in part to that, the painting focuses on the work and lives of peasants, as opposed to the royalty or the church.

Normally when we look at a scene, paint a painting, take a photograph, we stand in one place, we look out and that’s the scene that we see. It’s pretty normal.

We can also think about a panoramic photo where we stand in one place and we pan around to see a wide range, maybe 180 degrees, a large space, but still, we stand in one space.

However, Bruegel doesn’t do that. It’s kind of a reverse panorama. He starts us off in one spot towards the left, moves us towards the middle of the painting and then moves us to the right. What I mean by that is in terms of how we’re looking at the painting, how we as a viewer see the painting and see the figures and the spaces in the painting, it’s as if at first we’re standing to the left and then we move and we stand towards the middle of the painting and then we move over and we’re standing towards the right. So we’re looking towards the left.

It’s very unique. I really can’t think of any other painting that functions in this way and it achieves a very unique result. It achieves a very large space, a sense of grandeur, a sense of openness and largeness to the whole space, but it does it in quite a subtle way. Honestly, it’s hard to even notice that he’s doing this. When I looked at this painting for a long time, I never even noticed it and that’s part of the brilliance of this painting is that he’s shifting and changing how we see the space, but he’s holding it so that we don’t notice. He wants it to seem like a regular space, a regular painting, but he also at the same time wants to give us this very special feeling of space. It’s really quite brilliant and it has an effect, a palpable effect that we can feel without having to notice it. We don’t have to know what he’s doing to be able to feel what he is doing.

Let’s look for a moment at another painting that depicts a similar scene. The Wheatfield was painted by John Constable in 1816, 250 years after Bruegel’s painting. As we look at Constable’s painting, the general setting is similar. There’s a large expanse of wheatfield and workers laboring in it. The space in Constable’s painting is about what we would expect. The scene looks quite normal with the peasants working in the field in the front and the hills and clouds in the background. However, the feeling is quite different. If we take a bit of time to look at the painting, I think you’ll feel it as well.

In Bruegel’s painting, there’s a sense of grandeur. The scene feels large, much larger than in Constable’s painting. There’s a lot of history behind this painting and a lot of ways that we can approach discussing it. I want to talk about it from a slightly different point of view though, one that’s perhaps actually more common to each of us. I want to talk about the painting as if we had just approached it for the first time in the museum, not knowing anything about it. This painting lives in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, so we can imagine that we’re going there to take a look at it. There’s a few reasons for this approach. For one thing, I think we can learn a great deal about a painting in this way, in some respects, more than we can than by delving into the history, or at least we can learn different things. Also, it’ll teach us how to look at and analyze paintings in general. The more paintings that we analyze in this way, the better we’ll get and the more we’ll be able to appreciate other paintings that we see as well.

For me, the most amazing thing about this painting is how Bruegel handles the pictorial space and how he tells his story through that space. Pictorial space is the space in the picture, the sense of the space in the painting.

Some paintings have a large sense of space, such as this painting by Thomas Cole, View of Florence from 1837. In this painting, there’s a great deal of depth and we can see far into the background, even though the objects in the background become extremely small and hard to make out.

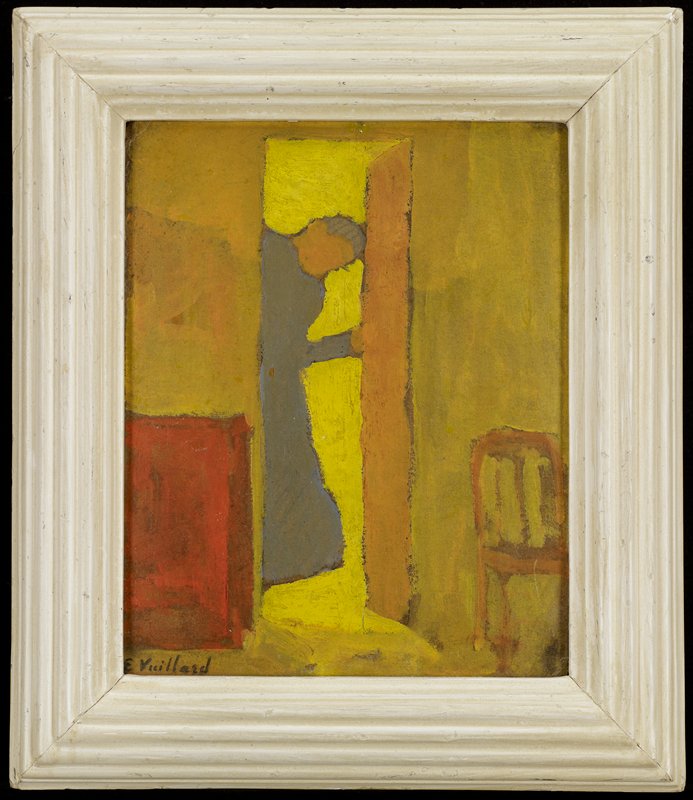

Other paintings have a much more limited focused sense of space, such as this painting by Edouard Vuillard, The Artist’s Mother Opening a Door from 1891.

But even within that, there’s many different ways to handle pictorial space. We’re probably most familiar with linear perspective, where the idea is to create an illusion of depth on a flat two-dimensional plane, similar to what we see with a camera. We see this in many paintings. It’s probably the predominant way of thinking in Western painting.

In the future, we’ll also talk about other perspective systems as well, such as what Matisse is doing in The Red Studio. This is not a painting that you can explain by linear perspective. In order to understand this painting, you really need to look at other perspective systems as well. But for now, we can stay more or less in the world of linear perspective. That’s where Bruegel mostly lives, although not exactly. He makes some interesting changes to linear perspective, and those changes help the painting to speak in a special way.

Though some people will say that we always enter a painting from the left, I think that there’s often multiple ways to enter a painting and to start moving through it. In this painting, it is probably most common to enter the painting in the lower left-hand corner. After all, there’s a big open space and a clear path, welcoming us to step into that area.

From there, we can move out in a few directions. We could move up the left side, or straight back into the background, or we can move up and around the right side.

On the left side, we’d likely follow the path, moving along with the peasants who are walking on it.

We could move past the hay cart and then either move into the center of the painting or up the second path and over towards the sea.

Alternatively, we might see the peasant carrying the water jug through the opening in the wheat fields. We could retrace his steps and follow them right out into the wheat fields beyond and then to the middle ground, where the monks and the townspeople play.

Most likely though, we’ll wind up and around to the right.

This movement is aided by a number of elements such as the blocks of wheat, which prevent us from moving past them, as well as the peasants in front of the wheat which block that route and guide us up and to the right.

Our eyes are also drawn by the peasants around the tree. The tree also helps to move us up and around the painting.

The hay lying on the ground also helps to move us up and around. Not only are they placed in an S-curve, but they also change orientation as they go up the side of the painting.

This helps us to feel that we’re subtly shifting our own position as we move up and around the scene. The blocks of the wheat field and the wheat on the ground continue all the way up to the right side of the painting, even crossing the tree line in the back.

We can see that Bruegel moves us around the painting, but he does more than this. He actually shifts the space in the painting. Normally when we look at a scene described through linear perspective, we only see that scene through one point of view. The way linear perspective works, it’s as if we stand in one place and we look out while covering one eye. No matter what, I look straight ahead. I don’t turn my head, nor do I look in a different direction with my eyes. If I want to look left, I look straight ahead and I see what falls in my field of vision to the left. If I want to look right, I still look straight ahead and I see whatever manages to fall into my field of view on the right. This is how a camera looks at the world.

Typically in a painting or a photograph, we’re used to looking at one vantage point, such as in this painting, “An October Day in the White Mountains” by John Frederick Kensett. This is a painting of the White Mountains in New Hampshire. The White Mountains in New Hampshire are beautiful, by the way, if you get a chance, I highly recommend going. As we look at this painting, we look out over the vista painted. We look straight out in one direction over the landscape. We don’t turn our head or change the direction we’re facing. Maybe the artist set up his easel there and painted the scene. That’s possible. He may have set up his easel in one spot and painted what he saw directly in front of him. Or maybe he made a number of sketches and smaller paintings before returning to the studio to paint the final painting. Regardless, this setup of Kensett’s painting is what we commonly expect, looking straight out over a scene, looking in one direction, and not turning our head or shifting the gaze of our eyes.

However, we might argue that we don’t really experience the world in this way. If we look at this painting by Cezanne, we might ask, “Why does the table look so strange? Why has he taken the table and broken it into two pieces, glued it back together, and then painted it?” In fact, the table is probably a fine table in one piece. However, he painted it this way in order to show how our perspective changes as we move around and look at a scene.

Let’s examine different parts of Bruegel’s painting and see how our point of view changes. We’re not going to look at every aspect right now, just at where our point of view lies and how it changes. After that, we’ll examine how he does this. That’ll give us some insight into what he’s doing and how he’s accomplishing it.

Some of these things may seem small and subtle, but that’s exactly the point. Bruegel was trying to create an effect without telling us that he was creating that effect. Remember that with linear perspective, our point of view from which we look at the scene, that point of view should not change at all.

Let’s start with the left side of the painting. Starting with the foreground, we see the water jug and the first and second peasant. Given the perspective from which we can see them, it looks as though we’re standing to the left side of them and looking at them from there.

Moving back towards the middle of the painting, we see a line of peasants walking into the distance. Although they’re moving back into space, we see them from the left side, not from the back or the right side. This is plausible due to how Bruegel arranged the landscape, but because we’re seeing them from the left side as if we were standing to the left of them, this would make more sense if they were arranged that same way, but they were located on the right side of the painting.

Arriving now in the background, we continue to see things as if looking from the left. Looking at the hay cart and the trees in the road, we’re seeing them as if looking from the left side. Notably, the size of the cart is much larger in comparison with the rest of the area. This shows its importance.

Color-wise, it also makes a connection to the foreground and background yellows. We’ll discuss the colors a little bit more later.

Looking at the peasant walking through the space in the wheat, we see both sides of the wall of the wheat. This would only happen if we were positioned there looking straight at him, with our vision able to see both sides of the pathway between the wheat.

So now we’ve gone from standing to the left of the scene to now standing more towards the middle, directly in front of that peasant who’s walking through the wheat field. This is strange when we consider that Bruegel has now taken us and shifted us from standing in one place to standing in another.

Looking into the background at the bridge, we can see that the sides of the bridge move at different angles. And in fact, the bridge opens to us more than it probably should. But this allows Bruegel to invite us into the town and open up that space.

As we continue around the painting, looking at the stacks of hay on the ground and the peasants around the tree, we start to look at them from the right side. We see the underside of the hay in a way that fits with standing further to the right.

Looking at the peasants around the tree, from the side of the woman in the yellow shirt to the woman drinking from the bowl and others around the circle, we see details of them that include the right side of their perspective, something we could not do if we had maintained the original position of being off to the left side.

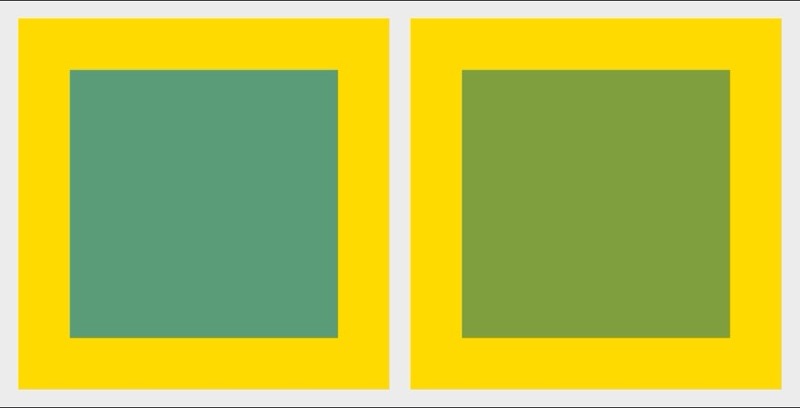

Aside from the perspective shift, Bruegel also has another method for controlling pictorial space, color. Notice the green at the mid-ground, as opposed to the reddish-yellow above and below it. The bluish-green in the mid-ground is separating from the reddish-yellow. If we change the green to a yellowish-green, we get a much different effect where the whole painting is more harmonious with less tension.

This idea of color movement and harmony and tension through colors is something that I go into detail in, in my book, Color Movement Theory.

Notice also that the monks and the townspeople are all in the bluish green area, whereas the peasants are in the reddish yellow area with mostly matching colors. This adds to the sense of separation between the lives of the peasants and the lives of the monks and the townspeople.

As I mentioned, a lot of these details are very subtle and really very easy to miss. The fact that Bruegel’s painting does not look strange and we have to work so hard to see what he’s doing is part of the genius of this painting. We can see how he winds us around from the left side up through the right side of the painting. What’s not obvious are the subtle shifts in perspective that give us this expansive feeling.

One of the reasons for this is that he takes care to capture our attention in critical spots so that we don’t notice the perspective and spatial shifts. For example, one of the perspective shifts we see is on the left side of the painting with the trees and the cart in the background. He uses the figures of the peasants in the foreground as anchor points. So as we move from one type of perspective or point of view to another, we don’t notice it so much as our attention is grabbed by the figure.

We can see this same technique in this painting by Liang Kai. When we transition from the first table to the second table, there’s a drastic shift in perspective and point of view. In part, this is enabled by the fact that it’s a horizontal scroll that would be unrolled as it’s viewed, but it’s also enabled by the figure between the tables. That figure captures our attention and allows the space to shift around them.

Let’s look at what happens if we remove the peasant walking in the gap between the wheat fields. Now we take the scene in in quite a different way. Our perspective in relation to the wheat field is much more obvious as we see both sides of the walls of the wheat. There’s also more of a jarring awareness of our shift in position.

Also, we’re much more likely to slip into the background following the gap in the wheat. This leads us straight back into the work rather than pushing us to wind around the space. By moving into one space in this way, we’re likely to feel a more traditional single focal point. And the space of the scene starts to feel a bit smaller as we’re focused more on one viewpoint.

Similarly, the tree serves not only to split up the space and bring our attention from the bottom of the painting up, it also serves to ease the shift in perspective as we move from the left to the right side of the painting. We can see that with both the peasant and the tree removed, the shifts in perspective while still subtle are much more noticeable as there’s now no sense of moving from one scene to another. Furthermore, our movement through the painting is less controlled. We can wander through various parts of the painting but there’s less of a sense of where to go. Also, the painting actually feels smaller to me in this way. It’s as if we took a three-part play and shrunk it down into a one-act play. Whereas in the original painting, there are separate scenes each with their own perspective and sense of space. There’s less clarity, less sense of direction, and the whole thing even feels smaller and a little bit more pressed together.

Despite these different scenes, there’s a flow and a movement that ties them all together, creating a unified, expansive feel to the whole work. This painting also makes use of a higher vantage point, which makes it easier to change the perspective without it being as obvious. We can see that Bruegel used a number of subtle but really brilliant techniques to tell a story, to create a feeling, to create a scene in a way that is subtle, in a way that we don’t necessarily notice it at first, but conveys very much what he wants to convey. And what he’s conveying, at least in part, is the importance of the work of the peasants.

It seems certain that Bruegel had some peasant background or he had connection with peasants or some kind of relationship with peasants. Certainly the peasant life was something very familiar to him and something important to him. We can see this in the fact that he’s painting about the life of peasants, the work of peasants, at a time when, as we said, a lot of the paintings was more religious in orientation. So he’s painting about the peasants’ everyday life and their work. It’s a very different topic. And as we can see from this painting, he’s showing us the importance of their work. Peasants are working in the field, there’s this grandness to the scene where they’re working, and the food, the wheat that they’re collecting, it moves out. Remember the relationship of the colors in the foreground and the background? It moves out and it goes out to the sea or the ocean, I’m not quite sure the body of water there, but they’re feeding the world this wheat, or at least wherever it’s being shipped to. This wheat is being collected and it’s going out and it’s feeding many people. So this is important work that the peasants are engaged in.

And we see that in contrast to how he paints the monks and the townspeople. And he doesn’t paint them in a negative way, certainly, but they’re playing, they’re skinny dipping, or they’re playing games in the field, they’re relaxing while the peasants are working in the field. So there’s a very definite contrast there as well.

One thing we’ve done in terms of how we’ve looked at this painting is we’ve understood it on its own terms. We didn’t go through a lot of art history, there is a lot of great writing about this painting and certainly deserves to be read and it’s deserved to be understood through that light. But we chose a different path. We chose, or I chose to share with you, but we chose to look at it directly, to imagine that we’re entering the museum and we’re looking directly at the painting. We can understand it directly through what the painting is saying, how it’s painted, what its language is, and how it’s communicating. And I think that’s very powerful in a couple of ways. For one thing, it allows us the opportunity to listen directly to what the artist is saying. It’s great to read and to research about work, but to be able to speak directly, as it were, to listen directly to the artist and what the artist was saying, I think that’s really very powerful. And to do that, we actually don’t need to do all the analysis that we’ve done. It’s enough to feel it, to take the time to feel how, or to feel the space, even if we’re not aware of how he’s shifting us, but to feel that grandeur. The analysis that we did, so where we’re understanding how he’s shifting space and how he’s using space and how he’s moving us around, that analysis helps us to understand this painting further, but I think it also helps us so that we can understand other paintings further as well. We can take what we’ve learned here, we can take how we’ve started to understand this painting, and we can use that idea in looking at other paintings. Not that other paintings are doing the same thing, but that we can use this way of thinking about space. We can use these questions. How is this artist approaching space? How is this artist shifting or changing space and color? What are the relationships like in this painting? And what’s the story that the artist wants to tell through all of that? I think this painting by Bruegel is one of the true masterpieces of the world.

Artwork:

Pieter Bruegel, The Harvesters at the Metropolitan Museum of Art https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/435809

Thomas Cole, View of Florence

https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1961.39

Edouard Vuillard, The Artist’s Mother Opening a Door

https://collections.artsmia.org/art/5091/the-artists-mother-opening-a-door-edouard-vuillard

Henri Matisse, The Red Studio

https://www.robertnajlis.com/matisse-red-studio/

Paul Cézanne, The Basket of Apples

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/111436/the-basket-of-apples

John Frederick Kensett, An October Day in the White Mountains

https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1967.5

Sericulture (The Process of Making Silk), attributed to Liang Kai

https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1977.5